June 2, 2018

Dear Members of the BBS Community,

I look forward to the opportunity to catch up with many of you at the upcoming BBS Family Association Conference later this month in Salt Lake City, Utah (actually just north of SLC). I recognize that many will not be attendance so I hope newsletters such as this will serve to keep you updated on important health care information acquired through the Clinical Registry Investigating Bardet-Biedl Syndrome (CRIBBS). I want to express my appreciation to the BBSFA for the longstanding support given to CRIBBS and your individual effort to donate time, money and kind words for our efforts of the Marshfield Clinic Center of Excellence for BBS.

I would like to share information that our team presented at the Pediatric Academic Society Meeting in Toronto, Canada the first week of May. This information I believe has importance that is relevant to the health care of individuals with BBS.

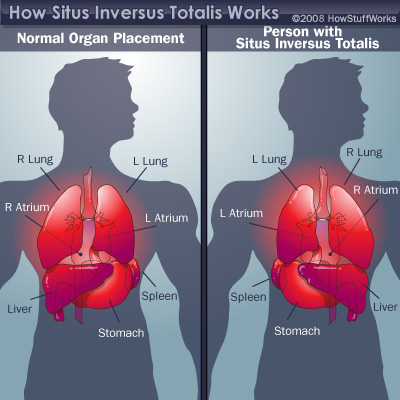

Early in the 21st century, Nico Katsanis, Ph.D. identified a person with BBS and situs inversus totalis. Situs inversus totalis means that organs in the chest and abdomen are positioned opposite of normal (mirror image of normal human anatomy). Knowing that disorders of cilia can cause situs inversus totalis, Dr Katsanis looked and discovered that BBS genes produced proteins that affect the cilia. Thus, BBS became known as a ciliopathy. His connection of situs inversus totalis, ciliopathies and BBS was a very important breakthrough in BBS research. In many references, situs inverus totalis is listed as a characteristic in BBS but the prevalence of this condition in BBS is unreported. Situs inversus has also been reported in other ciliopathies but is by far most common in a ciliopathy called Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) where it occurs in about half of all individuals with that ciliopathy. Using CRIBBS we set out to find the prevalence of situs inversus in BBS.

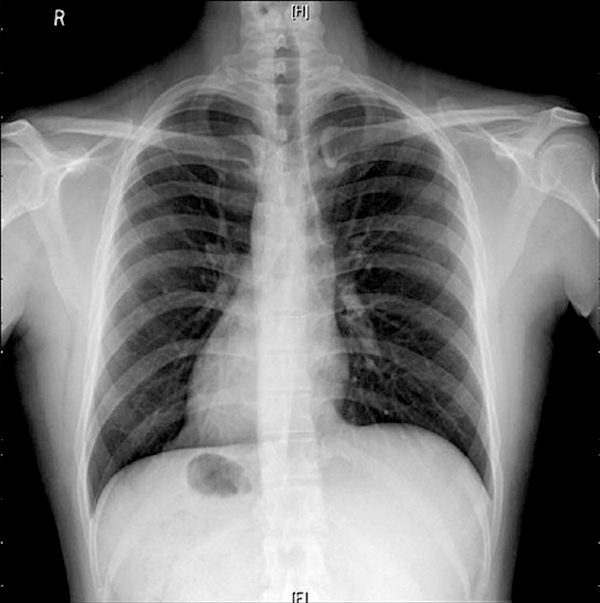

In the above x-ray, the heart is pointing to the right side and the black spot below the heart is the stomach. It is on the right side instead of the normal left sided placement.

Situs inversus totalis is considered the “classic disorder” of thoracic and abdominal asymmetry. There are other disorders of asymmetry of the organs in the chest and abdomen. The abnormalities can be much more significant and have more serious implications compared to situs inversus. These disorders are collectively called heterotaxy. In heterotaxy, some of the organs, but not all of them, are in the wrong place in the chest or abdomen. For example, the heart may be in the middle of the chest (mesocardia) instead of pointing to the left or right. There may be abnormal veins or arteries carrying blood to or from the heart. In heterotaxy, the intestines can be rotated in abnormal patterns (intestinal malrotation) or may have areas of blockage in the small or large intestine (intestinal atresia). Other birth defects such as an absent spleen (asplenia) or multiple spleens (polysplenia); shortened pancreas or abnormal wrapping of the pancreas around the intestine can be seen. Heterotaxy can be associated with abnormal development of the urinary tract and respiratory tract and may explain some of the findings in BBS.

Heterotaxy and situs inversus totalis occur in about 1 in 10,000 births in the general population. Employing data collected from CRIBBS we established a prevalence of 1 in 60 births. That is a 170-fold increase in disorders of asymmetry compared to the general population. Heterotaxy was twice as common as situs inversus totalis. Oftentimes, heterotaxy can be unrecognized if it is not associated with heart defects. That is extremely important because it informs you and your doctors of the importance of careful evaluation prior to surgical care. For example, a person being evaluated for kidney transplantation may need an altered approach to the procedure because of the large vein returning blood from the lower extremities (inferior vena cava) may be interrupted and the blood return may use alternative veins (azygos or hemiazygos veins). Or individuals with appendicitis may not have classic symptoms if their intestines are malrotated.

Another critical observation we reported at the Pediatric Academic Society meeting was that a person with complex characteristics of BBS and situs inversus or heterotaxy may have two separate ciliopathies. One of individuals we reported had overlapping features with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia and BBS. Genetic testing validated that the person had both a pair of BBS genes (homozygous mutations) and two pairs of PCD genes. A take home message is that complex issues you are experiencing should not always be attributed to BBS alone. Keeping an open mind is essential.

This information from CRIBBS has been presented in a poster that is attached. I recognize that the visually impaired will not be able to fully benefit from the attachment. My sincere apologies to those of you that cannot read the attachment. A paper informing physicians, especially pediatricians, of this valuable information will be published. Most importantly I want you to be aware that our aim is to use information from CRIBBS to better inform you and your providers of issues relevant to your health.

Thank you for your support of CRIBBS. If you have not joined CRIBBS or if you have not been available for follow up phone calls from Deb Johnson, my amazing research coordinator, please contact Deb at (877) 894-3499 or at CRIBBS@mcrf.mfldclin.edu or www.bbs-registry.org. The webpage www.bbs-registry.org has all past newsletters and a lot more. If you are interested in learning more about the BBS Center of Excellence and our care team please contact Sonia Suda at (715) 389-3235 or at suda.sona@marshfieldclinic.org.

Dr Bob Haws

Display in Latest News: Yes